Spoiler alert No. 1: This isn’t a story about Edward James Olmos. Well, not technically, anyway.

It’s a story about the Latino Film Institute, the nonprofit organization that Olmos founded, chaired and — when necessary — quietly paid for out of his own pocket. Its purpose is to celebrate and bolster “the richness of Latino lives” by providing “a launching pad from our community into the entertainment industry,” in the ambitious words of its mission statement.

It’s also a story about what is arguably California’s most innovative and successful education initiative of the last decade that you’ve probably never heard of: the Youth Cinema Project. The YCP grew out of the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival (LALIFF), the annual showcase that Olmos co-founded with Marlene Dermer and George Hernández in the 1990s, under the umbrella of the Latino Film Institute.

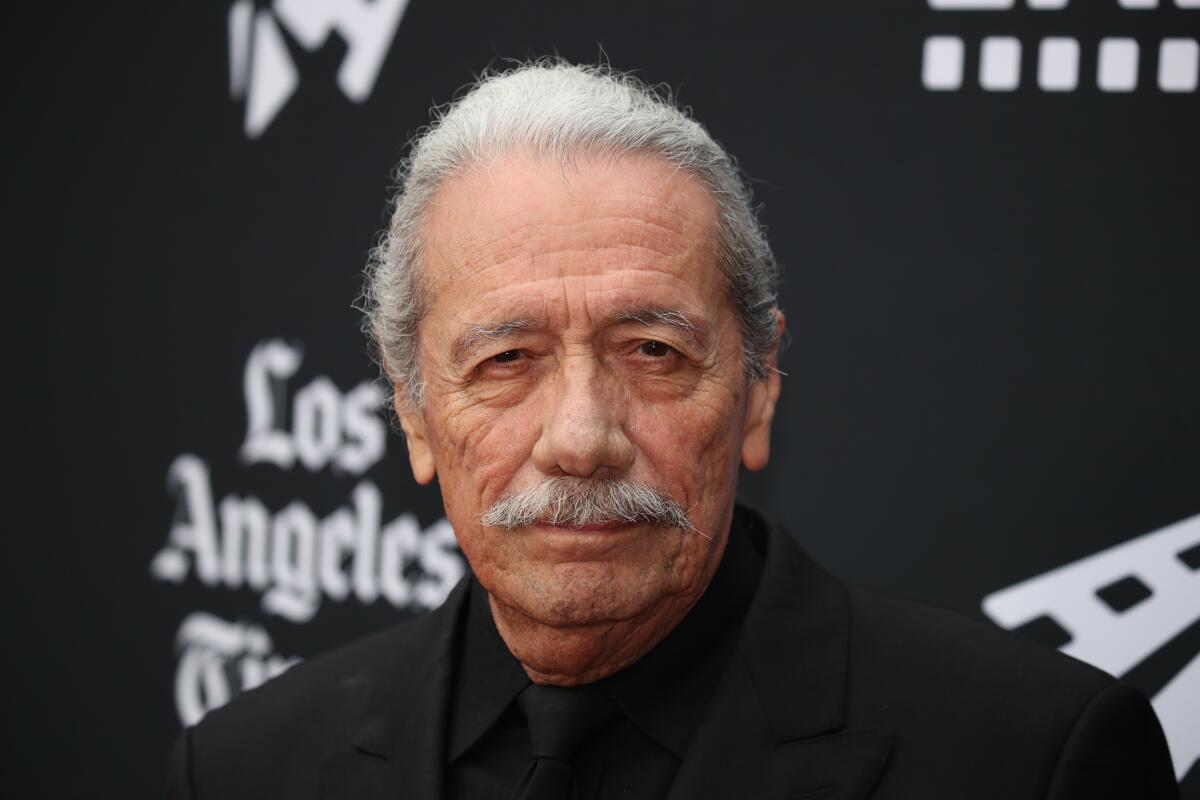

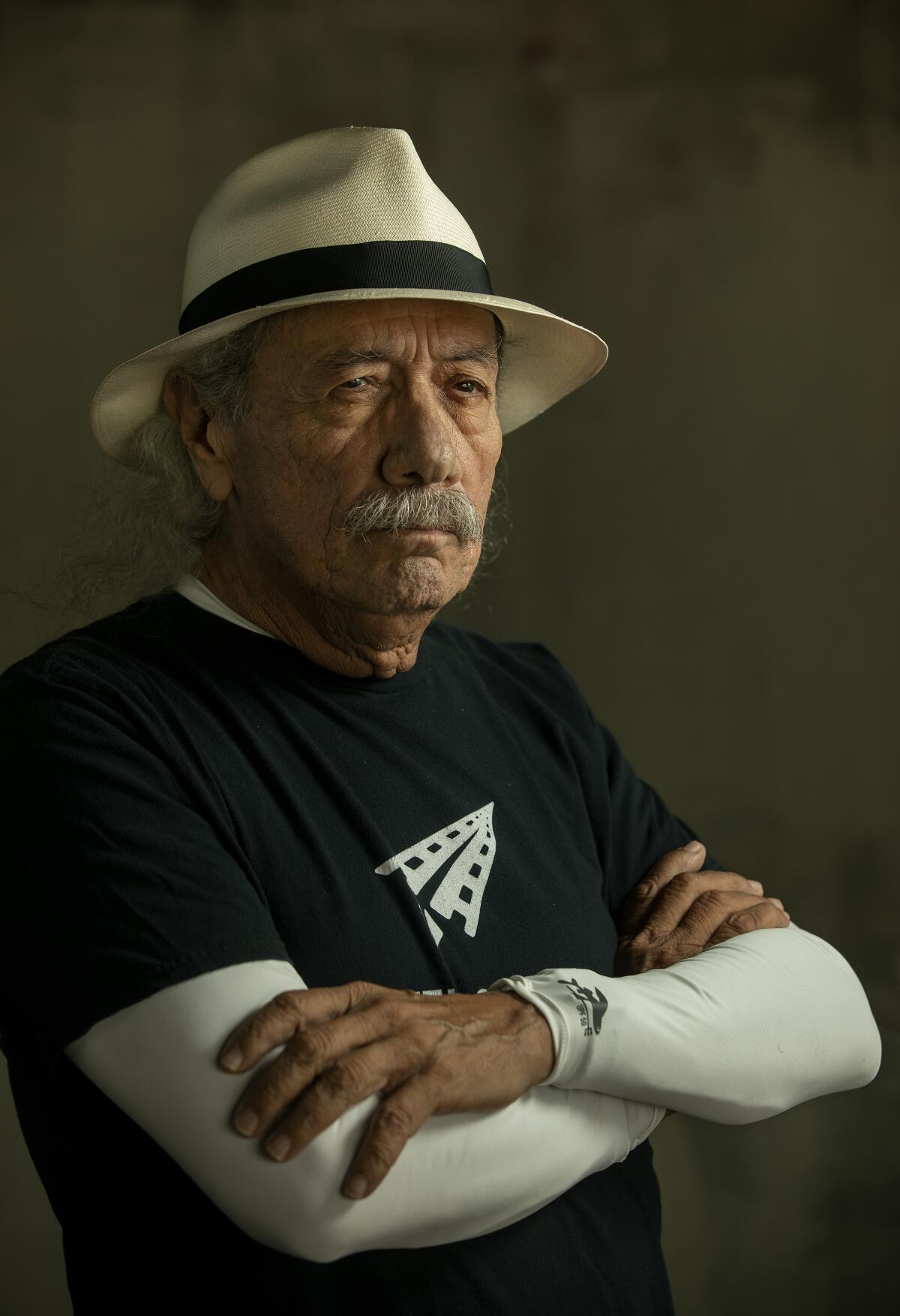

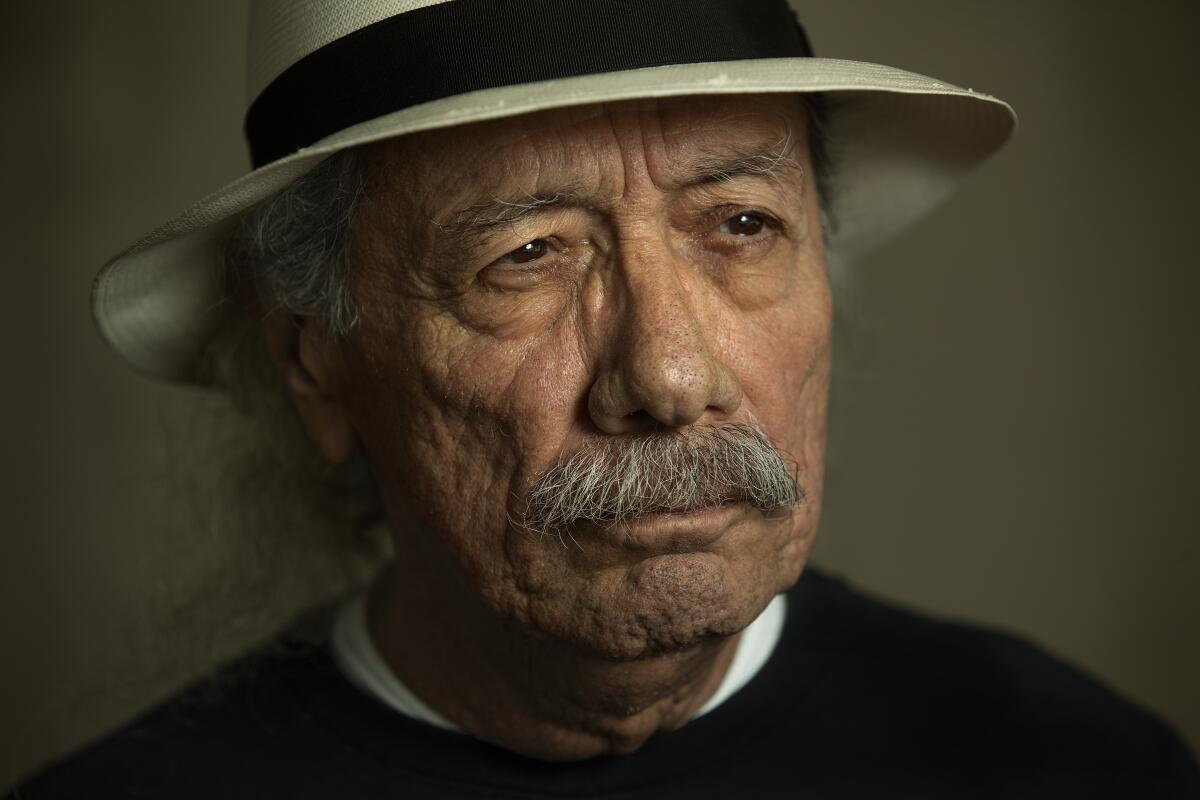

Actor Edward James Olmos is photographed in Burbank. Olmos recently announced he has beaten cancer.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

YCP, the film festival and LatinX in Animation are the Latino Film Institute’s three signature programs. If the Latino Film Institute is the launchpad, and LALIFF is the red-carpet attraction, the Youth Cinema Project is the organization’s maternity ward, its laboratory, its classroom.

It’s been known for decades that Latinos and other ethnicities are absurdly underrepresented in the film and TV industry. No news there. It’s been the same conundrum since before Olmos got out of East Los Angeles College in the early ’60s, when many Latino actors still were confined to bit parts as bandits and floozies, and the handful of bona fide stars often played down their Latinidad.

“Anthony Quinn still hadn’t come out as a Mexican yet. And Anthony Quinn was great, but he was doing ‘Zorba the Greek,’” Olmos said a few weeks ago over lunch at the Smoke House Restaurant in Burbank, a classic old-school joint popular with industry folk where even the waiters seem straight out of central casting.

For decades following his breakout role as the sleek and insinuating El Pachuco in “Zoot Suit,” while his own career rocketed upward with “Miami Vice,” “American Me,” “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” and “Battlestar Galactica,” Olmos lamented the lack of opportunities for other people like him.

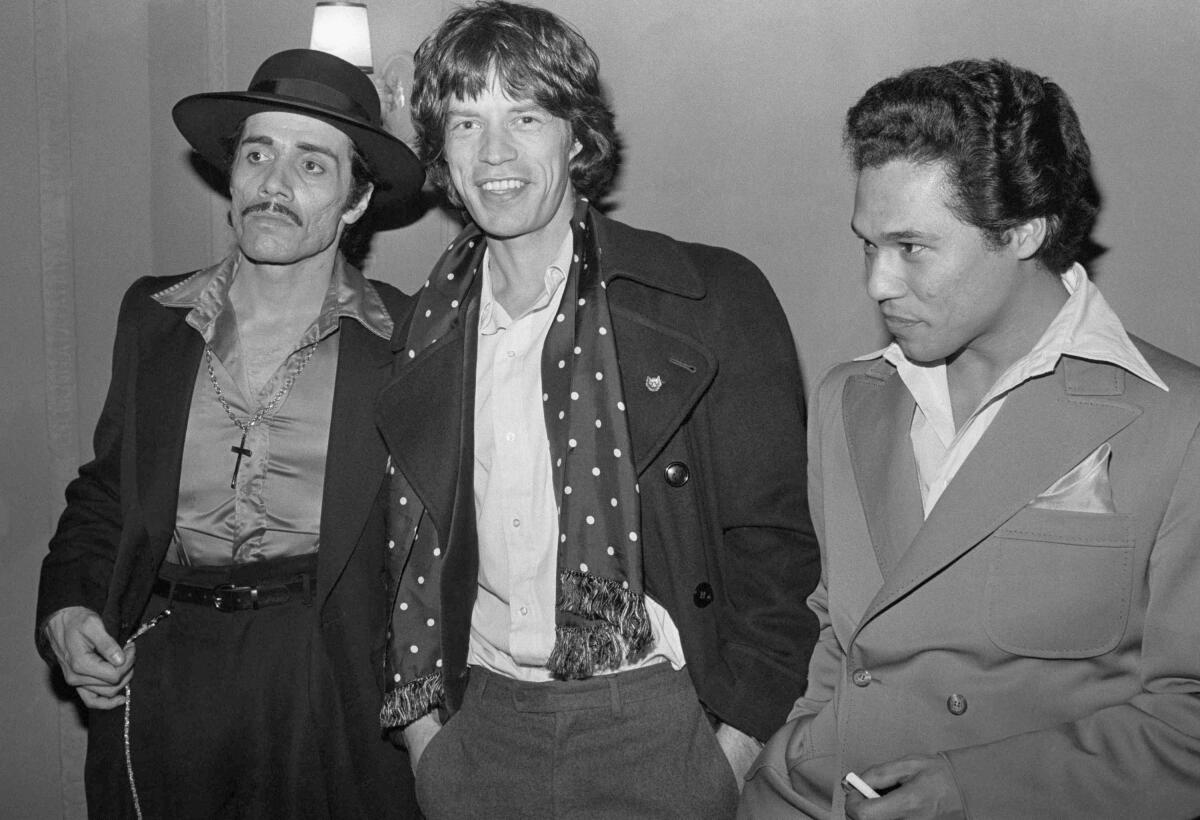

Edward James Olmos, left, hangs out with Mick Jagger and Danny Valdez backstage at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York on March 23, 1979.

(Richard Drew / Associated Press)

But instead of merely opining about this unsatisfactory state of affairs, he decided to create a pipeline for training California elementary and high school students to pursue careers in cinema: a nine-month, twice-weekly, 90-minute immersion program in which kids learn how to make a short film — between four and 15 minutes, depending on grade level — from conceptualization to script writing to shooting to postproduction. They receive state-of-the-art equipment and instruction from top industry pros. Their finished films are then screened each year at LALIFF.

“We never tell ’em what to write. We never tell them where to place the camera. We teach them how to use the camera,” Olmos said.

For many years, Olmos subsidized the film festival and YCP. He worked the phones to raise additional funds. He used his Hollywood contacts to inspire longtime artistic comrades to join in.

The only thing he didn’t do much was talk publicly about YCP and the institute’s growing breadth of activities — until now.

“We haven’t gone out and promoted ourselves and tried to sell ourselves,” Olmos said, sipping an Arnold Palmer. “What we’ve done is, we’ve done the work. And I’ve always been a true believer that when the work is really, really done well and you keep on doing it, it rises to the top. And people start looking in and saying, ‘Wow, where did this come from?’”

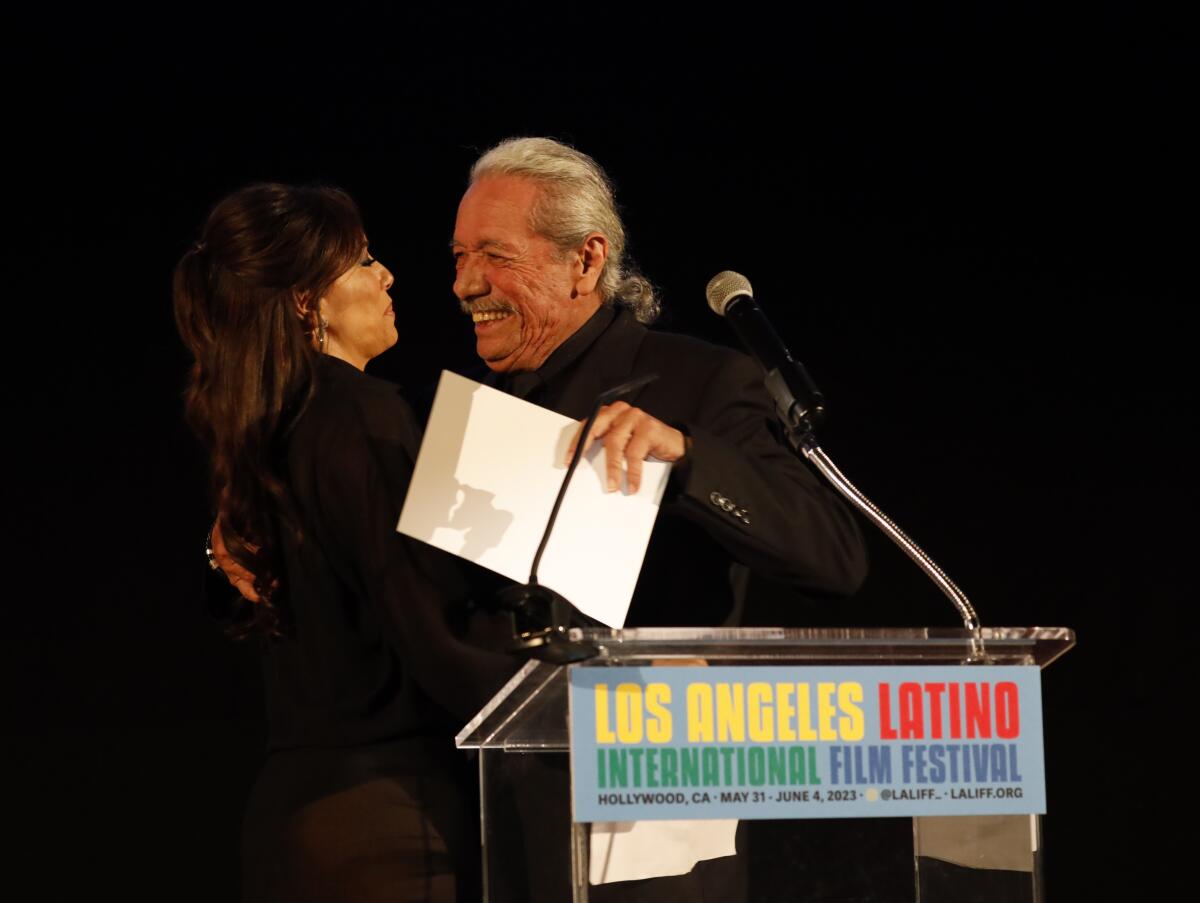

Edward James Olmos hugs Eva Longoria, director of “Flamin’ Hot,” at the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival last May.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

The Youth Cinema Project’s origin story is modest, momentous and a bit improbable, like the mythical Hollywood ingenue discovered at Schwab’s Pharmacy.

After launching LALIFF in 1998, Olmos and his partners worked out a deal that allowed students to ride Metro for free to attend festival screenings. As the festival grew into an essential venue for top cinematic fare from the diaspora — its contributors have included everyone from Pedro Almodóvar to Eva Longoria, Lin-Manuel Miranda to Alejandro González Iñárritu — Olmos and his team came up with the idea of launching a youth program within LALIFF. The idea was to promote literacy by forcing kids to read subtitled films.

It worked. Spurred by teacher and staff requests, they expanded the youth program by pairing students with professional screenwriters to help them create and develop story pitches.

After years of slow, steady growth, in 2014 Olmos and his colleagues took their education program directly into the schools, and the program took off. YCP started in the Santa Ana Unified School District and now operates in 16 school districts and 50 schools across California. Though it’s not specifically aimed at students of color or lower-income students per se, increasingly that’s become the core population of most California public schools, so that’s mainly whom the program serves.

About 1,700 kids will go through it this year. There’s already a spinoff program in Panama, and there are plans for further expansion.

“They want us in Arizona, they want us in Texas, they want us in Georgia, they want us in Florida, they want us in Chicago, they want us in New York,” Olmos said. “It’ll be a while before we can do that because this is not like building McDonald’s restaurants.”

YCP’s broader goal is to create lifelong learners with transferable skills — communication, collaboration, problem solving, critical thinking — that will serve them in whatever career they choose. Not every YCP graduate goes on to film school, but most go on to college.

Actor Edward James Olmos is photographed in Burbank. Olmos recently announced he has beaten cancer.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

“The most important thing for us was really the hands-on experience, and then also the folks that were coming in from Hollywood to work with the kids,” said Raul Maldonado, superintendent of the 77% Latino Palmdale School District, who learned about the Youth Cinema Project at a 2014 workshop and thought “this would be really cool for kids.”

Palmdale offers the program as an elective at its Desert Willow Magnet Academy and Dos Caminos Dual Immersion School, and this year is adding it at its Palmdale Academy Charter High School.

“They’re able to express their ideas, their stories, their journey, and that builds their self-esteem,” Maldonado said of the students.

Like others who’ve experienced YCP’s transformative synergy, Maldonado notes that one of Olmos’ signature roles, in “Stand and Deliver,” is Jaime Escalante, the Bolivian American calculus teacher who challenged his Garfield High students to shatter society’s low expectations of them. The role earned Olmos the only lead actor Oscar nomination for a Mexican American.

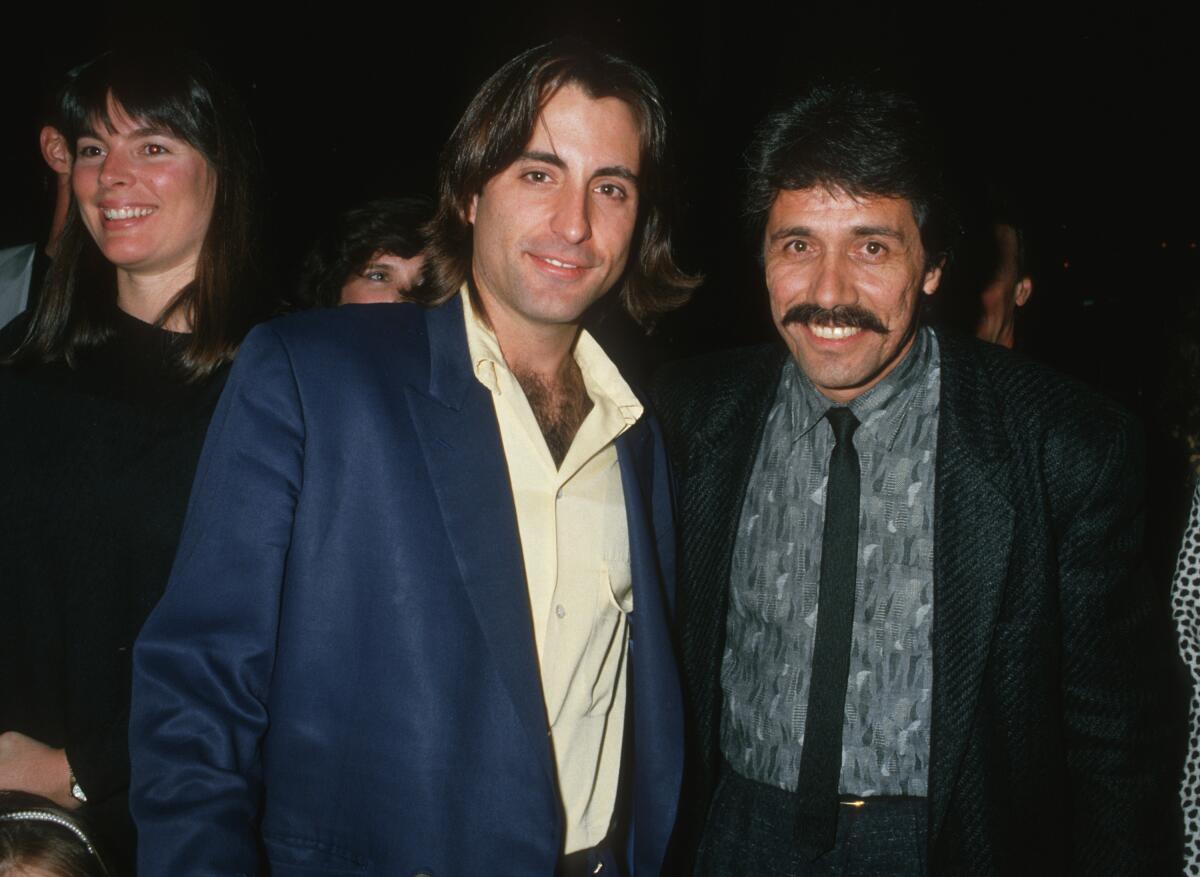

Andy Garcia and Edward James Olmos during “Stand and Deliver” Hollywood Premiere – February 26, 1988 at Mann Chinese Theater in Hollywood, California, United States.

(Ron Galella, Ltd. / Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Andy Garcia, who has known Olmos since the late ’70s and played opposite him in several key scenes in “Stand and Deliver,” remembers during promotion of that landmark 1988 film “how passionately Eddie spoke about all those subjects, and the furtherment of Hispanic-Latino stories, empowering ourselves to fight for the right to tell our stories, the space to tell it.”

“Eddie’s always been at the forefront of that,” said Garcia, who has shown several of his own films at LALIFF, including “The Lost City” (2005) and “Father of the Bride” (2022). “It’s like a life’s mission for him.”

As its influence spread, LALIFF picked up financial backing from the California Endowment and more recently from Amazon Studios, which awards $20,000 apiece to three works in progress by young Latina and Latino filmmakers. Amazon also sponsors a program to provide mentoring to 330 YCP “graduates” and funds a YCP alumni fellowship program.

Meanwhile, Netflix has partnered with LALIFF to create an inclusion fellowship that awards $30,000 each to 10 emerging writer-directors — five Indigenous Latino and five Afro/Black Latino — along with access to educational opportunities and mentorship from industry professionals. All 10 short films premiered at this year’s edition of LALIFF.

“The LALIFF team’s commitment to championing Latinx stories in the industry is exceptional, and we are honored to be partners with them in this work,” Pete Corona, Netflix’s director of drama series for the U.S. and Canada, said in a statement.

The Youth Cinema Project earned high praise in a 2019 independent report by the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity, which uses data and other research to help schools and school districts evaluate educational performance. The report’s authors concluded, “YCP holds great potential for impacting students’ lives as learners by effectively implementing the research based practices that support both academic learning and social emotional learning by creating positive climates in schools and classrooms, and engaging them in active learning communities that foster their social and emotional development.”

This year, the California Department of Education awarded the Latino Film Institute a one-time $500,000 investment for the Youth Cinema Project. Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles), who has championed legislation giving tax incentives to Hollywood to pursue more equity- and diversity-based policies, said in an email that she hopes that the funds she helped secure for the Youth Cinema Project will “help support the next generation of entertainment workers who look more like the city of L.A. and the people of California.” Carrillo called Olmos “a great thought partner, offering advice and insight.”

Ah, sorry, to repeat — this is not a story about Edward James Olmos, who agreed to do this interview only if it would focus on the Latino Film Institute and YCP, not on him. Coming from someone of his wattage, that request might smack of false modesty, like one of those humble-brag Oscar speeches that make you want to rip the flat-screen off the wall.

But, as his gravel-voiced gravitas suggests, Olmos doesn’t perform for the paparazzi.

Latasha Gillespie, head of global diversity, equity and inclusion at Amazon Studios, said that Olmos isn’t merely a figurehead for the institute and YCP but is “really on the ground and really involved with the students.”

“A lot of times you meet actors that are very different than the roles they play,” Gillespie said. “And of course, we can think of ‘Stand and Deliver,’ one of his most iconic roles. And being around him I felt that same spirit and energy. And you can tell that he doesn’t show it for a photo op. He genuinely, genuinely is personally committed.”

Latino Film Institute founder Edward James Olmos poses with, from left, actor-director Gloria Calderon Kellett, Youth Cinema Project executive director Erika Sabel Flores and Amazon Studios executive Latasha Gillespie at an announcement ceremony for Amazon’s partnerships with the institute in October 2022.

(Jc Olivera/Amazon Studios)

Spoiler alert No. 2: The story you’re reading almost didn’t have a Hollywood ending. That’s because at this time last year Olmos was battling throat cancer.

He beat it at the end of 2022, but it wasted him. He lost close to 60 pounds. The pain was almost intolerable. He writhed in agony at the dinner table and woke up gasping every night, urgently pulling the mucus out of his mouth so he wouldn’t choke to death. At certain moments he’s still convulsed by coughing fits.

Virtually none of his closest friends and colleagues ever knew. Olmos didn’t tell them until he was out of the woods, and didn’t go public until last May.

Why so stoic and silent? “Nobody would’ve been able to do anything except worry,” he said.

Like Olmos, it wasn’t always clear that the Latino Film Institute would survive.

By 2014, the Youth Cinema Project was accelerating and needed a much bigger investment and commitment from school districts, students and superintendents. Olmos had been tirelessly meeting with district officials and their boards, showing that the program not only helped students to learn the syntax of cinema but also to nurture self-confidence, draw on their own creativity and, for some, practice a language that wasn’t spoken at home.

At one school in Northern California, 30 out of 32 students tested out in English proficiency after taking part in YCP.

“We brought in project-based learning, we turned around and destroyed the concept of, ‘OK, open your books to Page 34,’ and ‘Look at the board,’ and, ‘Everybody’s attention over here, please, look at the teacher,’” Olmos said.

Then a crisis hit. Despite its bounty of high-quality films (about 130 each year), LALIFF, the festival, was sagging under the burden of the economic downturn. Though it received some corporate sponsorship, including from the Los Angeles Times, it had relied too heavily for too long on Olmos’ personal patronage.

A one-year cancellation turned into a four-year suspension from 2014 to 2018.

“We shut down the film festival and people got hurt. The community got hurt,” Olmos said. “They said, ‘How can you do this, you can’t shut down.’ I said, ‘We have to, man. We’ve been trying to hold it up, and we reach out and we ask you guys to come and buy a $5 ticket and it’s always like pulling teeth.’ We used to make about $80,000 to $100,000 in 10 days of [screenings], and the thing was costing us $800,000 to rent that big a place and bring in the best films in the world.”

Bringing LALIFF back from hiatus was going to be a heavy lift, after four years of shedding audiences and sponsors. But because the Youth Cinema Project was by then turning a profit, its funds could be used to revive the film festival. In effect, the child organization became the parent, and LALIFF reopened in 2019.

Olmos beat throat cancer last year, but even close friends never knew he was ill. “Nobody would’ve been able to do anything except worry,” he says.

(Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times)

Students who go through YCP speak of it as life-changing.

“I always wanted to be in the arts when I was younger, and people, my family, told me I’ve got to figure out something that will make sure money,” said Emily Magan, 14, who joined the program as a seventh-grader at Monseñor Oscar Romero Charter Middle School in L.A.’s Pico-Union neighborhood. “And it was a big shift when I got more serious about film, and they were telling me to follow my heart.”

Emily said YCP mentors helped her strive and grow through every stage of making her short film, a magical-realist fable inspired by her sadness over the prospect of her brother leaving home. Her middle-school teachers helped Emily balance her complex schedule and meet all her commitments.

This year she was awarded a $40,000 Herb Alpert Scholarship for Emerging Young Artists, which she’ll put toward studying film in college.

“I had no idea there was a presence of Latinos in film before,” she said. “I think in this age we have much more access to creating films and sharing our stories.”

Daniela Alarcon didn’t know any English when her family immigrated to the U.S. from Guatemala. YCP helped her master a new language while she made a film that she later submitted as part of her application to Cal State Northridge, where she’s now studying film as a freshman.

“I learned that communication is a big part of this industry,” she said.

Olmos and his colleagues believe they’ve discovered a partial solution to #OscarsSoWhite. But it’s not changing voting rules for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It’s entities like the Latino Film Institute and programs like YCP.

“What’s going to happen to all these things in 50 years?” Olmos asked. “Are they going to be gone, in the past? Or are they going to be institutions that can honestly preserve, prevail and extend it to the future?

“We don’t have the opportunity to fail,” he added. “If we fail, it knocks us back 30 years.”

Spoiler alert No. 3: The next page of this screenplay won’t be written solely by Edward James Olmos (whom this story wasn’t about), or by the expanding multilingual creative community he has built from scratch.

There still are some missing actors who will need to enter the frame: The studio executive who applauds the hypothetical notion of making more Latino films and TV shows but won’t shell out to sustain them. The politician who thinks arts programs for school kids are frou-frou compared with STEM subjects.

As Jaime Escalante might’ve put it, they only see the turn. They don’t see the road ahead.